King Lear

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

— King Lear, III, ii

Trytel

It was just me, blowing my nose. Once again I have, may it not happen to you—a cold.

— The Jewish King Lear, III

Great Divides

Rifts between parents and children haunt the poetic imagination. Perhaps our every action and thought—social, political, certainly familial—can be seen as a referendum on an parental model, inviting the security of approval, the dread of punishment, or the thrill of defiance.

Jacob Gordin’s watershed Der Yidisher Konig Lir, dove headlong into these roiling waters in 1892 New York: it is a play about a familial divide, a play written in an adopted country for an immigrant community already redefining itself in relation to its Old World parents, a play about a religion deeply invested in family tradition, and a play itself inspired by a work of the father of the adopted country’s theater. Works of art, too, have parents—those works come before, in whose likeness the new are consciously and unconsciously made.

The Jewish King Lear is NOT Shakespeare’s Lear translated into Yiddish. (It’s first star, Jacob Adler, played Lear in Shakespeare’s play to great acclaim, but that is merely icing on this particular cake.) It is a transplant of Lear’s predicament into another culture and another time, exploring poignant themes for its author’s people, articulating his ideals, and offering, as it strays from Shakespeare’s tragedy, a hope for a future enlivened by the great works of the past and enlightened by the social and scientific progress of its present.

Prosperous Lithuanian merchant, Reb Dovidl Moysheles, divides his worldly possessions among his three daughters before retiring to a pious life “in the study of Torah and prayer.” The youngest daughter questions his plan: she and her beloved tutor even compare him to a character in a play by “the world-famous writer Shakespeare.” In response, Dovidl casts her from his house.

But as years pass, he finds his two eldest daughters and their husbands treat him as beggar in his former home. Filled with pride, consumed by remorse, and nearly blind, he now casts himself from his house, with only the company of his devoted, if irreverent, servant.

And yet, in that same time, his “ungrateful” daughter has committed herself to studies of her own, and in her hands this tragedy takes a surprising turn…

Seems Familiar . . .

To lovers of Shakespeare, the correspondences with Lear offer particular gifts. Dovidl is the irascible, loving, short-sighted king; his servant Trytel, the ironical Fool; daughters Etele and Gitele, the grasping Goneril and Regan; truth-telling daughter Taybele, his modest Cordelia; while her loving tutor, Herr Yaffe, is a youthful, clear-sighted Kent. (The Gloucester family is essentially discarded.)

But the diversions from Lear hold the fascination and edification of the play. To see the familiar story in 19th century Eastern European Jewish context is continually surprising and illuminating. This “Lear” has a wife, for example, whose suffering deepens the pathos of the family’s errors while offering hope of comfort throughout. Moreover, the play’s hopeful ending, , in which foolishness is forgiven, evil is punished, and loving unity restored, though disappointing to the lover of tragedy, serves a very different purpose for its intended audience.

Gordin’s tale of a family’s struggles with arbitrary authority addressed challenges confronting 19th century Jewish communities worldwide. Born into the Haskalah movement—the “Jewish Enlightenment” that encompassed both an adoption of modern European customs and a rejection of many traditional Jewish practices—He embraced what we might call progressive ideals, and the play is an impassioned argument for them. In Dovidl’s failings, a father’s and a tradition’s domination over his family is challenged. The elder daughters’ ungrateful households indict two ideological branches of traditional Judaism: Etele has married a Misnagid; Gitele, a Hasid, and both husbands are depicted as superstitious and self-serving: the one rigorous, cold-hearted, and hypocritical; the other weak, self-indulgent, and addled by mysticism. Meanwhile, Taybele’s pursuit of learning and social utility affirm a woman’s right to self-determination, to education, to a life engaged with the world—more a character from Ibsen than from Shakespeare. Her tutor Yaffe’s self-possessed rejection of traditional obeisance and promotion of practical behavior, scientific discovery, as well as refined arts are instructions for the modern Jewish man, and they are clearly the voice of the playwright.

19th century immigrants to New York saw themselves in the play. Inspired and enabled to reconstruct their lives, but struggling mightily with attachments to families and traditions left behind, they all played one role or another in Dovidl’s rebellious household.

They also would have seen that the play itself was rebellious : against stage traditions. Yiddish Theater thrived on New York’s Lower East Side from the 1890’s to the 1930’s as a meeting place for a community drawn from across Eastern Europe and discovering itself anew in America. But before Gordin, a typical production was an operetta, a sensational comedy, or an heroic tale, delivered in a heightened stage language, a Germanized Yiddish called Daytshmerish, and peppered with shtick, song, and ad-libs. Gordin brought a naturalistic sensibility to his work, and insisted on writing for all his characters in everyday Yiddish. His work addressed real people’s problems in a familiar language. Such a theater could be a window through which to examine vexing issues of acculturating life, from labor relations, to women’s rights, to personal relationships. The Jewish King Lear was a breakout hit for him and Jacob Adler’s company, with Adler in the title role.

World Premiere

Metropolitan’s production is not exactly the play that Adler’s audience saw, but closer to Gordin’s original. Adler’s company introduced its own revisions and excised a crucial final scene. We are honored to present the premiere of not only a lively and sparkling new translation by Ruth Gay, but one that comes from Gordin’s own 1891 manuscript.

The result is at once both familiar and strange. Filled with pathos and humor, and resonant with both old cultural and old stage traditions, it captures for Jewish and Gentile audiences the wrenching conflicts between ancient customs and new inspirations. Under the direction of Ed Chemaly, the production will be buoyed up with adaptations of traditional song led by renowned scholar, singer, songwriter, and actress Amanda (Miryem Khaye) Seigel.

A theatrical classic transformed into another culture’s play; an introduction to Metropolitan’s stage of a vital American theatrical genre; a revival of a groundbreaking work, but in a never-before-staged text; and simply a story of a family torn asunder by arrogance and error, but reunited by love and devotion, The Jewish King Lear is the ideal play to conclude our 26th Season, the Season of Resilience.

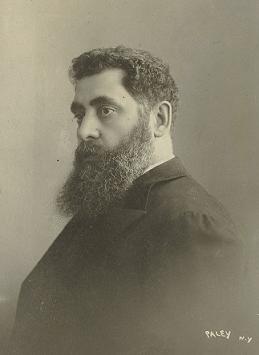

Jacob Michailovitch Gordin (1 May 1853 – 11 June 1909), born in Myrhorod, Ukraine, was already a recognized Russian writer and journalist when he emigrated to America in 1891. He is often credited with transforming Yiddish Theater through realism and melodrama and bringing the art form, previously dominated by frivolous Purim plays and hastily written comedic operettas, to a new level of maturity.Heavily influenced by the literary and introspective institutions of Europe and Russia, Gordin’s work does not shy away from the complexities of human behavior but examines them, adding depth, personal history, and motive to the figures on stage. Consequently, his plays were the first in the theater to make wide ranging use of the formidable skills of Yiddish-American actors.Such a theater also gave audiences an opportunity to see themselves and their plight represented on stage. Like the lens of his contemporary Jacob Riis, Gordin’s plays became a vehicle for a kind of social documentary, one that shed light on the lives of working class immigrants and exposed the indignities of daily existence and the sting of systemic injustice.

Jacob Michailovitch Gordin (1 May 1853 – 11 June 1909), born in Myrhorod, Ukraine, was already a recognized Russian writer and journalist when he emigrated to America in 1891. He is often credited with transforming Yiddish Theater through realism and melodrama and bringing the art form, previously dominated by frivolous Purim plays and hastily written comedic operettas, to a new level of maturity.Heavily influenced by the literary and introspective institutions of Europe and Russia, Gordin’s work does not shy away from the complexities of human behavior but examines them, adding depth, personal history, and motive to the figures on stage. Consequently, his plays were the first in the theater to make wide ranging use of the formidable skills of Yiddish-American actors.Such a theater also gave audiences an opportunity to see themselves and their plight represented on stage. Like the lens of his contemporary Jacob Riis, Gordin’s plays became a vehicle for a kind of social documentary, one that shed light on the lives of working class immigrants and exposed the indignities of daily existence and the sting of systemic injustice.

Still, political social commentary was not what drew his audiences. Gordin had a gift for showing people the richness of their human dramas in a way that was believable and recognizable. Audiences flocked to his plays to see themes they understood and cared about, such as modern dilemmas concerning filial piety, sexual and social mores, work, family and religious observance, brought to life before them. A frequent adapter of well-known classic plays and stories, Gordin had a knack for seeing towering literary archetypes in their familiar Yiddish counterparts and vice versa.

The Jewish King Lear (written in 1892) was Gordin’s first play to be both a critical and popular success in America. It drew a new crowd of Russian-Jewish intellectuals to the theater and firmly established the significance of Gordin’s contribution to the art form. Later, in 1902, another of Gordin’s adaptations, The Kreutzer Sonata (based on Leo Tolstoy’s novella of the same name) became the first Yiddish play to be translated into English.

Gordin’s signature realism differed from that which we recognize as realism today. Nevertheless, as Russian Literature professor Barbara Henry notes, “[Gordon’s] innovations shifted expectations about form, language, and subject matter, and they showed younger writers what might be done further.”

Jacob Gordin died on June 11, 1909 in New York City. Though seldom performed, his work survives in dozens of texts, memoirs, and reviews, in Yiddish and in translation.

Translator

RUTH GAY

The late Ruth Gay wrote extensively on Jewish history and culture. Her books include Safe Among the Germans: Liberated Jews After World War II and The Jews of Germany: A Historical Portrait, both published by Yale University Press, and Unfinished People: Eastern European Jews Encounter America, published by W. W. Norton.