The trouble with conventional success is all the work involved, which is why we at Metropolitan so admire those who have awakened from the wearying and wasteful “American Dream” to quicker and easier ways to riches. And as we have seen in the financial headlines this year, one of the favorites is selling something you don’t actually have. From the grifter on the corner hawking a brick in a VCR box to the investor on the Street pruning an empty hedge fund, offering nothing for something is a well-used method of making it without lifting a finger.

The trouble with conventional success is all the work involved, which is why we at Metropolitan so admire those who have awakened from the wearying and wasteful “American Dream” to quicker and easier ways to riches. And as we have seen in the financial headlines this year, one of the favorites is selling something you don’t actually have. From the grifter on the corner hawking a brick in a VCR box to the investor on the Street pruning an empty hedge fund, offering nothing for something is a well-used method of making it without lifting a finger.

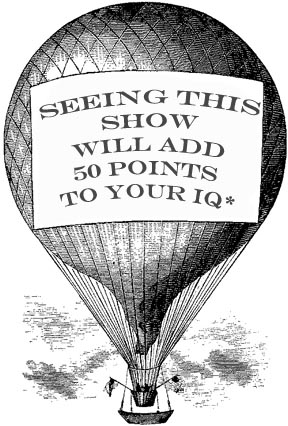

How do you sell what you don’t have? Advertise.

In Megrue and Hackett’s quick-witted 1914 comedy, Rodney Martin has a problem: to please his industrial giant father and win the enterprising girl of his dreams, he has to make something of himself. But with no experience, he only has will without way. Welcome old chum Ambrose Peale, a fast-talking pitchman for a Broadway flop who can always spot an opportunity where it isn’t. Together, they hatch a foolproof scheme: found a company, promote that company, sell that company, and never make anything at all. The key to it all is advertising: you don’t need to make a product if you can make a name.

Advertising is as old as persuasion (Be smarter! Try the apple!) From handbills to storefronts, wagon-sides to soapboxes, town squares to circulars–anyone with an idea or a product will create an advertisement, but around the end of the 19th century, two forces came together to create the advertising Americans know and….love.

On the one hand, newspapers had exploded throughout the century. Advances in printing techniques made papers affordable for most of the populace, and as the industrial revolution took off, the number of titles grew practically exponentially. But ads for the most part were more like what we our classifieds, with no images and even little variation in type.

It was the development of the methods of mass production–creating gluts of cheap goods of consistent quality–that led to an evolution in advertising. Maufacturers had to solve the problem not of providing what people needed, but convincing people they needed what the manufacturers could too easily provide. From Wanamakerís in Phildelphia, to MAcy’s in New York to Marshall Fields and Sears, Roebuck in Chicago, the urge to advertise was irresistable to any good capitalist.

It is this world that Megrue and Hackett write for, and it is not so unlike our own. Underneath the fast-paced, light-hearted comedy is a social transformation. Old Cyrus Martin knows how to build a business, but he doesn’t believe in flashy advertising. Rodney and Ambrose know nothing about manufacture, but they know about image. And both the sharp-eyed secretary Mary Grayson and a conniving Countess de Beaurien (trans. Beautiful Nothing!) see the opportunities the others miss–usually for better than for worse. Success lies in bringing their different perspectives together. This charming collection of characters is never quite what they seem, but all have a good pitch, and in weaving their lives together, the popular comic writers create a very smart play with a sharp wit and a gentle bite.

As the final production of our Season of Work, we are proud to revive a funny, maybe too-timely, comedy-romance from the treasure-trove of American theater.

Your satisfaction is guaranteed or all your money back!*

MEGRUE and HACKETT

It Pays to Advertise was the only collaboration between two prolific men of the theater. Novelized in 1915, turned into a silent movie in 1919, and then re-made in 1931 (with Carol Lombarde and Louise Brookes in a role that does not exist in the stage version), the play has had a long and vital life. Even Metropolitan has presented an adaptation, by Mark Hirschfield, who moved the action to the ’70’s in 1997.

New York born Roi Cooper Megrue (1883-1927), was known for popular melodrama and light-hearted comedies, and his credits as author or co-author included Under Cover(1914), Under Fire (1915), Potash and Perlmutter in Society (1915) and Tea for Three (1918). His 1916 comedy Seven Chances was even reborn in 1999 as the Renee Zellweger/ Chris OíDonnell film, The Bachelor. Megrue produced and directed as well, and it was his production of Jesse Lynch Williams’ Why Marry? that won, in 1918, the first ever Pulitzer Prize for drama.

Walter C. Hackett (1876 – 1944) wrote or co-wrote many numerous plays that went on to become films, including Freedom of the Seas, Regeneration, Hyde Park Corner, The Gay Adventure, and Other Men’s Wives. Together with wife Marion Lorne, best known now, perhaps, from her turn in Strangers on a Train or as Aunt Clara from the TV series Bewitched), he founded London’s Whitehall Theatre (now Trafalgar Studios) in 1931.

* This is quite untrue.