What is it about a melodrama? Why can’t we resist sighing with the plucky heroine, cheering the sterling hero, and best of all, hissing the unrepentant villain? Why do we want to see an innocent tied to a railroad track?

What is it about a melodrama? Why can’t we resist sighing with the plucky heroine, cheering the sterling hero, and best of all, hissing the unrepentant villain? Why do we want to see an innocent tied to a railroad track?

Perhaps the melodrama is the purest form of theater: an extreme enactment of our fears and hopes. Originally, the word described a play (drama) underscored with music (meloidia.) Illustrating and driving the story’s emotional content was a natural outgrowth of an increasingly popular theater, as it played to the audience’s hunger for emotional exercise. Theatrical form may have evolved in an ironic age, but condemnation of plot contrivances and easily understood characters with clear motivations is a churlish refusal to join in the fun. And melodrama is, of course, alive and well–in soap opera, thriller, disaster/action/spy movie–where the good are very good, the evil very evil, and the plots dependent on twists and surprises that make the world darker and darker before a barely-hoped-for dawn.

But melodrama as sensational entertainment is only part of the story. The best of these rollercoaster rides of pathos take their audiences on purging journeys of pity and fear, where the subjects of the stories are (pace Aristotle!) seldom gods and royalty, but rather the same people who might form their audience. Perhaps for this reason, while the lively form of entertainment was common to America and Europe, its particular realizations bore the hallmarks of the national character.

Under the Gaslight is a distinguished American, defining the genre and living up to all expectations: a young New York socialite, on the cusp of her wedding, is visited by a black-clad figure from her hidden past, and her true identity is exposed. In shame, she flees censorious high society to eke out life in tenement squalor–but she is ferreted out by both her still-faithful suitor as well as her lifelong nemesis. Claimed by both worlds she embarks on an odyssey of high and low stations, aided by a band of loyal and scrappy allies including a cherubic street urchin, a wise-cracking proto-Bowery boy, and a one armed veteran of the Civil War whose payment is to be…tied to a railroad track before an onrushing train! (This scene—the play’s ‘sensation scene’—is the first instance of this particular device, and Daly sought, unsuccessfully, to defend it by copyright.)

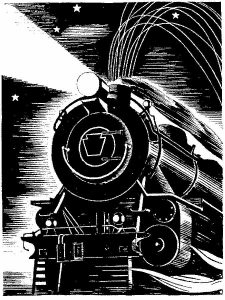

Juxtaposing the extremes of contemporary New York, à la Dickens and Hugo, Daly’s lavish spectacle is a type of truthful exposé. It tours New York from upper class salon to a tenement basement; from a seaside resort to a Hudson River pier; from Delmonico’s to The Tombs. Doing so, the play brought New York audiences face to face with very real contradictions in their current lives, and it evoked through its capricious turns of events some very real fears. The fragility of comfort and love is felt by every character. The threat of a fall from society’s grace is palpable. A striving criminal class threatens the well-off. Unseen menace lurks in every scene. And the famous onrushing train? A symbol of alienating modernization and the very real, often destructive changes wrought on communities by the spread of the railroad.

Implicit in the anxiety is social critique: not only is this a world of dangers, but one with rigid rules enforced by capricious officers. Social class defines and constrains each character, often in defiance of moral or intellectual worth. The upper class are typically vain, fickle, and a bit dim, while the (non-villainous) tenement dwellers are selfless, constant, and resourceful, but breeching the gulf between them invariably results in cataclysm. Poverty is a remorseless jailer, borne with good humor by some and with burning resentment by others. The law is inviolable, though not particularly just. And the importance of adhering to authority’s rules —such as those governing the actions of railway employees—is sufficient excuse to permit murder.

Is there no hope? Certainly there is, for fidelity, however tested, is rewarded in the end. Thus loyal friends find their hearts united, their petitions for compassion granted, or their lives saved by the same circumstantial fortune that tied them to the tracks in the first place.

The melodrama is in this context a true portrait of the arbitrary fortune that defines our lives. Some are born to luxury, some to penury. Our efforts to improve our lot meet dumb and implacable resistance in the form of social prejudice. Our struggles are abetted and opposed, but by the rather clumsy and shortsighted agents of our fellow men. And success or failure is ultimately subject to twists of fate as fickle as the wind. Separating this melodramatic world and a nihilistic dystopia is an underlying confidence that, ultimately, good will be rewarded and evil either punished or at least denied.

Under the Gaslight’s spirit has its roots in a cynical view of human life tempered by an optimistic faith in a righteous order. Perhaps melodramatic expression was a rather accurate portrayal of post-Civil War America in the later 19th Century…and perhaps not so terribly far from our own.

In any case, it is good fun. The bold lines—simple characters, preposterous plots, happy endings—are irresistibly entertaining. For the second production in our Season of Starting Over, come sigh, cheer, and hiss Under the Gaslight.

Augustin Daly was one of the grandest theatrical impresarios of the late 19th Century and is considered by many as the first modern American director. He began his career as a drama critic for several New York papers while penning plays such as Leah the Forsaken before the smash success of Under the Gaslight. He went on to manage successful venues such as the Fifth Avenue Theatre, and Daly’s Theatre in both New York and London and created his own company of actors. Known for his sensational effects, modern treatment of the actors in his company and a propensity for extensive alteration of even the most sacred theatrical works (such as Shakespeare), Daly was a driving force in American theater for nearly half a century.

-Alex Roe