Director’s Notes

The 19th century temperance movement in America was generated by social and economic change. Through the 18th century, distilled spirits were an integral part of American life, often augmenting monetary wages as compensation for labor, and drinking during the workday was common. But, as the 19th century progressed, liquor came to be seen as an impediment to the health of the country and its citizens. The new industrialists were concerned about inebriated workers and excessive absenteeism. Wives and mothers were concerned that their husbands, now leaving their homes and villages for new work places in the cities, were often stopping at pubs on the way home. In fact, women led the way in the temperance movement, which was closely allied with the nascent women’s movement in America. It is interesting to note that the temperance movement was, in fact, a progressive movement, also allied with the antislavery movement. Many theatres that produced The Drunkard also produced Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the pre-eminent antislavery drama of its day.

Around the time of The Drunkard, there were two significant developments within the movement that affected the play. For one, in an effort to effectively reach lower economic classes, including illiterate citizens, temperance workers discovered the emotional impact of theatre as a persuasion more effective than the arguments of printed material or the lecture circuit. To that end, temperance dramas, packed with sensationalistic, “affecting” scenes aimed at the heart of the viewer, became an important weapon in the battle against “Demon Rum.”

At the same time, as the movement began to include more adherents from the working class, the focus of blame for effects of alcohol shifted increasingly to those entrepreneurs (distillers, grocers, and barroom owners) who profited from its distribution. They were portrayed (as were slave owners in abolitionist dramas) as enslaving others to alcohol for the sake of self-interest and profit. The Drunkard offers Squire Cribbs, who leads our hero astray for greedy and licentious reasons, as an embodiment of such evil, capitalist self-interest.

Why produce The Drunkard in 2010? Certainly it is interesting as a theatrical artifact of the temperance movement, informed by a value system in many ways foreign to our contemporary culture. But it also carries a bold, emotionally charged theatricality not often found in 21st century drama outside of musicals. Our authors (W.H. Smith and an unnamed evangelistic collaborator), working to craft an engaging entertainment in the service of their mission, gave us a full palette of characters and situations we can still enjoy.

– Frank Kuhn

On The Drunkard at Metropolitan

In 1844, W. H. Smith opened The Drunkard at the Boston Museum, and playing the lead, he enjoyed 140 performances—the most successful run to that date in American stage history. The play also sired a family: the temperance drama, with more than 100 children. 160 years later, Metropolitan brings you this exceptional theatrical feat to begin our 19th Season: the season of “Stereotypes.”

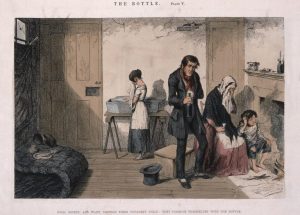

Edward Middleton is a virtuous and promising young man in his rural town, graced with a generous nature and a good humor. But his love of life embraces a fondness for drink—not a fault in itself, perhaps, but a taste turned against our hero by an indisputable villain. Squire Cribbs, cunning and duplicitous lawyer, sets his sites on stealing Edward’s property and happiness, both. To effect his malintents, he tempts Edward to a drink, and the young man’s journey begins from the country taverns to the city bars to a lonely hovel in a New York alley, a phial of poison his only possession and death his only friend.

Will his life end here? Is there no redemption? Please see the subtitle. The temperance play, an art of instruction, was set within the promise of salvation. (It is generally assumed, in fact, that Smith had a co-author for the play as well, most probably the Unitarian minister John Pierpoint.) Accordingly, there is a longer journey to take than a descent. More importantly, there is also a bigger story in the play than Edward’s drink.

The temperance movement was born of institutions confronting the industrial age: crew-oriented businesses were concerned about absenteeism and flagging productivity, while formerly home-based communities saw their factory-laboring men making tavern stops part of their “commute.” The Drunkard’s genius is setting a bucolic paradise of mid-century, hearth-centric America against the challenges presented by contemporary life. To achieve a world view, the play paints a picture of a colorful world, cast with characters whose foibles and virtues are all their own: the besotted Miss Spindle, in love with her fantasies; the earnest William, in love with words he does not understand; the doting matriarch Mrs. Wilson, adoring mother and widow; and a pastoral collection of farmers, lovers, children, and checkers players.

In this world, social vices run deeper than drunkenness. Greed and resentment are Cribbs’ motivations; falsehood and manipulation, his weapons. Gullibility, vanity, and ambition are the failings he exploits, and alcohol is more a catalyst for dangerous reactions than a menace itself. Meanwhile, though each of the untarnished characters in the play is sober, their true virtues are constancy, honesty, and generosity. From the honest but oafish William to the demure and faithful Mary to the saving angel Rencelaw; all are distinguished by clear vision and open hearts.

Indeed, the play makes spirited use of the distinction between man—who can enjoy fraternity, compassion, and refinement of social commerce—and brute, who cannot. If alcohol is to blame, it is for its reduction of good people to something less than human. Accordingly, the villain’s reward is embittered solitude; for the virtuous, there is familial embrace.

That reformers saw theater as a fitting medium for social improvement is something of a turnabout from the longstanding assertion—particularly by our puritanical forebears—that theaters were dens of vice. But these crusaders understood that it was only by marrying the message to the popular art form that they could reach a broad public. Preaching sermons is an ineffective way to reach a segment of society that has stopped going to church. Later generations have enjoyed their own versions of such cautionary tales—the cult favorite Reefer Madness or the later and rawer Trainspotting highlight the dangers of addiction.

Is a “message” play good theater? In this case, the agenda of the play is what gives it its theatrical panache. Its moral stance is the engine of the conflict, the source of the colorful characters, and the glass through which it makes its penetrating social perceptions.

As such, The Drunkard is bigger than this one of its parts. It is a wonderful celebration of one of theater’s most effective devices: to use a short-hand of character traits to reveal complex human truths. That is, the play makes game use of Stereotype for its theatrical punch, and it is an ideal first venture in our 19th season.

-Alex Roe, Artistic Director